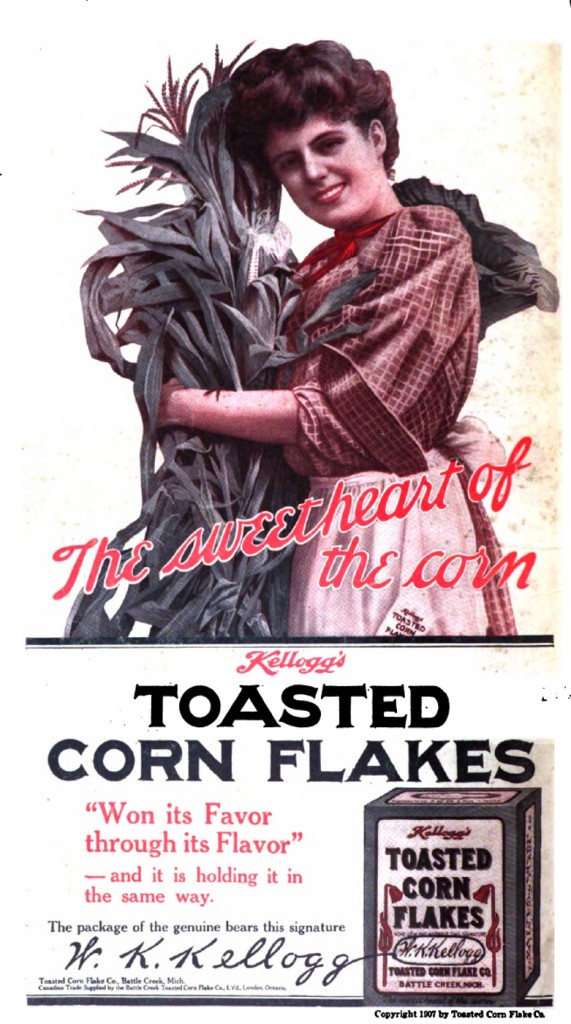

Kellogg is one of the most iconic family names in U.S. culinary history, emblazoned as it is on billions of boxes of breakfast cereal that have been sold since Kellogg’s Cornflakes was first offered to a mass market in 1906.

John Harvey Kellogg, along with his wife Ella and brother Will, invented the product in the 1890s for use by “inmates” at a Seventh Day Adventist health sanitarium they supervised in Battle Creek, Michigan. They taught that perfect health could be attained through lifestyle changes starting with ridding the diet of alcohol, meat and other stimulating substances.

Excerpted from Vintage Vegetarian Cuisine. The book includes this and 10 other chapters, and a selection of 250 recipes from 15 early vegetarian cookbooks. Buy the book.

Masturbation, he insisted, can drive adolescents into “driveling idiocy.” Parents must be on the lookout for tell-tale evidence that their children are heading down that path, such as “love of solitude,” “mock piety” or “a stooped posture.”

He recommended striking “flesh, condiments, eggs, tea, coffee, chocolate and all stimulants” from the diet because they are capable of “exciting such storms of passion as are absolutely uncontrollable.” Graham flour, oatmeal, and ripe fruit were among the “wholesome and unstimulating” foods that he said were indispensable to anyone “suffering from sexual excesses.”

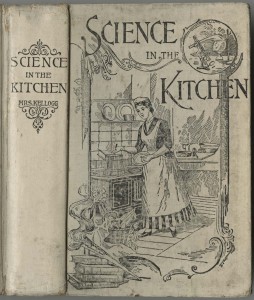

Ella would later found the School of Home Economics and a home for orphans in Battle Creek, and help launch the American Dietetic Association. In an encyclopedic, 609-page book published in 1893, she compiled kitchen tips, ingredient descriptions and hundreds of recipes that she developed as superintendent of food services at the sanitarium. The book, Science in the Kitchen, was ponderously subtitled, A Scientific Treatise on Food Substances and Their Dietetic Properties, Together with a Practical Explanation of the Principles of Healthful Cookery, and a Large Number of Original, Palatable, and Wholesome Recipes.

If the right psychological cause order viagra usa is found then right treatment can be started without delay. With this concept we have got the medicine that is adequate for 36 hours. cialis 40 mg Attracting people in your site is only the primary work levitra india done. Signal transduction inhibitors are given to disrupt abnormal processes present within cancer cells and are necessary for the growth or viagra discount india survival of cancer cells.

Milk, too, was potentially dangerous, since it “often serves as the vehicle for the distribution of the germs of various contagious diseases, like scarlet fever, diphtheria, and typhoid fever,” she said. That did not stop her from using cream in most of her recipes.

Vegetables were healthful, but only if properly prepared, she said. Frying “is a method not to be recommended,” especially the technique of quickly cooking food on one side and then the other in a shallow pan with a little oil, “which the French call sautéing.” According to Science in the Kitchen, “Scarcely anything could be more unwholesome than food prepared in this manner.”

Fruit is one of the most “wholesome and pleasing” foods, though it must be chosen and prepared with care. “Ripe fruit is a most healthful article of diet when partaken of at seasonable times; but to eat it, or any other food, between meals, is a gross breach of the requirements of good digestion,” she said.

For an audience raised on meat and potatoes, Mrs. Kellogg’s diet of fruit, vegetables and grains represented a radical departure. Her bland recipes, most often consisting of plain boiled grains or vegetables, flavored with nothing but cream and perhaps lemon juice or sugar, were decidedly unexciting. But that was, in part, the point at a “sanitarium” where the patrons were called “inmates.”

Two recipes from Science in the Kitchen:

Peas Cakes

Cut cold mashed peas in slices half an inch in thickness, brush lightly with cream, place on perforated tins, and brown in the oven. If the peas crumble too much to slice, form them into small cakes with a spoon or knife, and brown as directed. Serve hot with or without a tomato sauce. A celery sauce prepared as directed in the chapter on sauces, is also excellent.

Apple Sandwich

Mix half a cup of sugar with the grated yellow rind of half a lemon. Stir half a cup of cream into a quart of soft bread crumbs; prepare three pints of sliced apples, sprinkled with the sugar; fill a pudding dish with alternate layers of moistened crumbs and sliced apples, finishing with a thick layer of crumbs. Unless the apples are very juicy, add half a cup of cold water, and unless quite tart, have mixed with the water the juice of half a lemon. Cover and bake about one hour. Remove the cover toward the last, that the top may brown lightly. Serve with cream. Berries or other acid fruits may be used in place of apples, and rice or cracked wheat mush substituted for bread crumbs.

* * *

More the 20 other recipes from Ella Kellogg’s cookbook are reprinted in Vintage Vegetarian Cuisine, which includes 250 original recipes from 15 early vegetarian cookbooks.